Wood Turners Lumber

The number of wood species available for wood turning is potentially everyone in site, if sufficiently large. Wood turning lumber is different than conventional lumber as conventional lumber generally lacks enough thickness to be used for face grain turning. Its fine for segment and spindle turning, but often larger dimensions of material is needed. Most suppliers only stock a handful of wood species at 12/4 or thicker.

As such, wood that is used for bowl and vessel work is often gathered, processed, and dried by the turner. That means, nearly any species of wood is available to work with. Every part of the tree is also usable depending on the project, some parts of the tree work better for some things than others.

I work with over thirty wood species, many of them common in the southeastern United States. The vast majority of them come from central and eastern North Carolina, so I have lots of access to wood spanning multiple habitats.

All hardwoods have varying degrees of hardness and densities. Softer hardwoods make the best choice for utility pieces, as they are less prone to cracking during their lifetime. Sassafras is a good example as it is medium grained, on the softer side for shock resistance, turns like butter, and sands extremely well. All species work well for decorative and sculptural work, although some are more stable than others.

Where to find wood for Turning?

In my region Red Maple is certainly the most common and most of them have some degree of ambrosia in the tree. They are also one of the quickest to spalt, and the most common trees to burl. In general I look for any species of wood that is a fruit or nut hardwood. Historic towns or old homesteads are also a good place to find interesting wood. Its more common to find obscure wood species of ornamental, flowering, or fruiting trees that have lived long enough to develop usable size.

In my region Red Maple is certainly the most common and most of them have some degree of ambrosia in the tree. They are also one of the quickest to spalt, and the most common trees to burl. In general I look for any species of wood that is a fruit or nut hardwood. Historic towns or old homesteads are also a good place to find interesting wood. Its more common to find obscure wood species of ornamental, flowering, or fruiting trees that have lived long enough to develop usable size.

As an example I believe this is a Photinia Serrulata (Chinese Photinia) a subspecies of red tip that isn’t native to North Carolina. I noticed it last year as I placed my beehives nearby and they were all over the tree. This tree is probably pushing 100 years old and the trunk is close to two feet across, certainly large enough to turn.

Field edges are another one of my favorite spots due to greater species variability and fertilizer run off. Birds spread seed more readily along the edges of a field so its more common to have varying species of trees. Those trees also get more fertilizer run off and grow larger more quickly. Additionally those trees fall more frequently in storms or are subject to be taken down as growers don’t want large trees shading their fields.

Field edges are another one of my favorite spots due to greater species variability and fertilizer run off. Birds spread seed more readily along the edges of a field so its more common to have varying species of trees. Those trees also get more fertilizer run off and grow larger more quickly. Additionally those trees fall more frequently in storms or are subject to be taken down as growers don’t want large trees shading their fields.

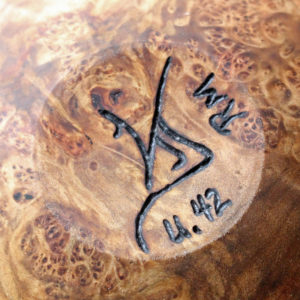

When I sign a piece I also put a species mark that corresponds to the legend, the picture shows the bottom of a cremation urn.

Utility Wood Species

Walnut

Cherry

Red Maple

Magnolia

Rock Elm

Box Elder

Sycamore

Sweet Gum

Poplar

Cottonwood

Red Bay

Hackberry

Chinaberry

White Ash

American Elm

Winged Elm

Black Gum

Catalpa

River Birch

Mulberry

Holly

American Beech

Mimosa

Green Ash

Total Wood Species Legend

Red Maple (RM) Acer rubrum

American Beech (B) Fagus grandifolia

Black Walnut (W) Juglans nigra

Black Cherry (C) Prunus serotina

Red Mulberry (RMB) Morus rubra

White Mulberry (WMB) Morus alba

Chinese Elm (CE) Ulmus parvifolia

Magnolia (MG) Magnolia grandiflora

Pecan (PE) Carya illinoinensis

Hickory (HI) Carya tomentosa

Red Oak (RO) Quercus rubra

White Oak (WO) Quercus alba

Chinaberry (CB) Melia azedarach

Holly (HO) Ilex opaca

Persimmon (PM) Diospyros virginiana

Dogwood (DW) Cornus mas

Rock Elm (RE) Ulmus thomasii

Chinese Chestnut (CC) Castanea mollissima

Box Elder (BE) Acer negundo

Sycamore (SY) Platanus occidentalis

Sweet Gum (SG) Liquidambar

Tulip Poplar (POP) Liriodendron tulipifera

Cottonwood, eastern (ECW) Populus deltoides

Cottonwood, western (WCW) Populus fremontii

Honey Locust (HL) Gleditsia triacanthos

Rock Maple (HM) Acer saccharum

Red Bay (RBY) Persea borbonia

Mimosa (MI) Mimosa turneri

Hackberry (HB) Celtis laevigata

White Ash (WA) Fraxinus americana

Bradford Pear (PR) Pyrus Calleryana

Black Locust (BL) Robinia pseudoacacia

American Elm (AE) Ulmus americana

Winged Elm (WE) Ulmus alata

Black Gum (BG) Nyssa sylvatica

Catalpa (CT) Catalpa bignonioides

River Birch (RB) Betula nigra

Green Ash (GA) Fraxinus pennsylvanica

Basswood (BW) Tilia americana

Water Tupelo (TU) Nyssa aquatica

Eastern Red Bud (RD) Cercis Canadensis

Wood Burl and Crotches

Occasionally while wood gathering I come across some burl in the tree. A burl is a growth defect on the tree that results in an abnormal formation. A wood burl formation in a tree is generally the tree’s natural response to some external influence, usually resulting from injury, insect damage, disease, mold, fungus, etc.

Occasionally while wood gathering I come across some burl in the tree. A burl is a growth defect on the tree that results in an abnormal formation. A wood burl formation in a tree is generally the tree’s natural response to some external influence, usually resulting from injury, insect damage, disease, mold, fungus, etc.

While a burl can look somewhat grotesque on the outside, the distortion in the normal grain pattern usually leads to very dramatic and colorful figure in the wood (Figure 1-3). The grain distortion in the burl is usually perpendicular, or off angle, to the regular grain direction of the tree and is what, visually, forms the patterns of the swirls and/or packed clusters of nodes.

Its more frequent, in my area, to see burls that develop in low or swampier areas. I suppose thats due to more external or environmental pressures on the trees, i.e. presence of mold/fungus, insects, etc. Its typical to see the growths on the trunk portion of the tree. The particular species may influence where the burl develops as well. Some wood species only tend to grow root burls, i.e. black walnut, and others grow on any part of the tree. Its also common to see multiple trees of the same species develop burls that are in the same general location.

Its more frequent, in my area, to see burls that develop in low or swampier areas. I suppose thats due to more external or environmental pressures on the trees, i.e. presence of mold/fungus, insects, etc. Its typical to see the growths on the trunk portion of the tree. The particular species may influence where the burl develops as well. Some wood species only tend to grow root burls, i.e. black walnut, and others grow on any part of the tree. Its also common to see multiple trees of the same species develop burls that are in the same general location.

Crotches are another potential area of the tree where distinctive figure is found. I also really like to turn crotches as every species of tree has them and its pretty much a sure fire place to find some figure in the tree. The area where the tree forks leads to a distortion in the normal grain pattern, as those two grain directions have to come together. While there is generally nice figure in that area, the wood also tends to be extremely unstable and usually moves more rapidly as it dries. I like to turn some hollow forms and let them warp, so this wood works well for that purpose. I also have found that the crotch of a tree tends to spalt more quickly, so its possible to find nice figured wood and different colorations from the spalting. The wood direction changes in crotches so its a bit trickier to turn cleanly.

figure is found. I also really like to turn crotches as every species of tree has them and its pretty much a sure fire place to find some figure in the tree. The area where the tree forks leads to a distortion in the normal grain pattern, as those two grain directions have to come together. While there is generally nice figure in that area, the wood also tends to be extremely unstable and usually moves more rapidly as it dries. I like to turn some hollow forms and let them warp, so this wood works well for that purpose. I also have found that the crotch of a tree tends to spalt more quickly, so its possible to find nice figured wood and different colorations from the spalting. The wood direction changes in crotches so its a bit trickier to turn cleanly.

Spalting and Ambrosia

Aside from the general figure in wood, spalting and ambrosia are two other things that I look for in trees. Spalting is the visual evidence that the tree has been subject to fungus/mold and the very early stages of decay. This will result in random patterns developing in the wood, as well as the  possibility of multiple colors (Figure 4).

possibility of multiple colors (Figure 4).

The coloration often is influenced by the specific wood species and the mold or fungus that has started to attack the tree. Certain species of mold and fungi are more common in certain trees. I.e. blue stain in pine and maple, blue-green stain in holly, red stain in a limited number of wood species, etc. The trade-off, however, is that spalting does start to deteriorate the quality of the wood, so heavily spalted wood can be too decayed to work with well.

Ambrosia is very similar to spalting in that it is a staining of the wood left by a fungus. The fungus is carried by the Ambrosia beetle, which bores into trees, and helps the fungus spread. As a result the tree will typically develop long streaks or stripes of blues, reds, and yellows (Figure 5).

Ambrosia  develops almost exclusively in maple trees, while spalting occurs in all trees, though the effects are more pronounced depending on the species of tree. Since spalting and ambrosia develop due to the presence of fungus and mold, it is most common to find in wet environments and high humidity climates.

develops almost exclusively in maple trees, while spalting occurs in all trees, though the effects are more pronounced depending on the species of tree. Since spalting and ambrosia develop due to the presence of fungus and mold, it is most common to find in wet environments and high humidity climates.