7.29.21 – Apiary Size – Mid/Late summer 2021

1.25.21 – End of Season 2020

9.18.20 – The Fall Nectar Flow

9.1.20 – Finishing out the Summer

6.15.20 – The start of the June dearth

4.22.20 – Tracking the Nectar Flow for NC Honey

3.27.20 – Double Deep Swarm Box

3.24.20 – Gearing up for Swarm Catching

I started a permanent treatment free apiary in Wake County, NC in 2018. Now a few years into it, this post catalogs the journey of creating a treatment free apiary in central North Carolina. I think that keeping honey bees without any form of treatment produces the purest form of North Carolina honey products. If your looking for raw North Carolina honey you check out the order form.

7.29.21 Apiary Size – Mid/Late summer 2021

Two Box Small Hive Configuration

Going into the winter of 2020 I overwintered 20 colonies in my apiary. Most of those colonies were small in size due to splitting hives very aggressively. Many of those hives ended up overwintering somewhere between a 4 over 4 to 6 over 6 deep frame configuration. I run 8 and 10 frame boxes so these small hives take up about half of two stacked boxes. The top box in the picture is a top feeder. This was the second winter since transitioning to a treatment/chemical free apiary. Thus, I am in the throws of high winter mortality as survivor genetics are established. Its typical to have 70-90% mortality the first year followed by 50-70% the second, 35-50% the third, 25-35% the fourth, 15-25% the fifth year and so on once treating for varroa mites is stopped.

All of that said I lost seven colonies last winter which gives me a mortality rate of 35%. Far better than what I was expecting, which was about a 50% loss. Additionally, it’s nice to confirm small hives of that size can overwinter successfully in my area. Current apiary size in Wake County is somewhere around 20 colonies. It may be a little lower than 20 going into the winter of 2021. Time got away from me and I manually split a few hives around the second week of July. In hindsight that was a mistake, as that left a few colonies very weak and easily overcome by the extreme robbing going on right now. The month of July is the peak of the summer dearth around here. Wax moth also set in very quickly on these collapsed hives. Learned that lesson the hard way.

Large Honey Bee Swarm Organizing

Moving forward, any splits that happen next year I will do by the first week of June. That should allow sufficient time for a new colony to become queenright by the end of the month. Hives that swarm out after June appear to be more likely to collapse due to the looming robbing pressure. From what I have noticed about swarming colonies is the old queen moves out with the primary swarm before the new queens emerge. That leaves the parent colony queen less, with fewer bees, and likely a lot of honey in the hive as they are coming out of the spring flow. As the nectar flow ends that leaves those colonies in prime position to be overrun. Whatever is left of the parent colony seems to get killed off or they abscond due to the raiding. Either way those later swarming colonies don’t seem to replace with a newly laying queen quite as frequently.

Excluding those manual splits I made, nearly all of my colonies have swarmed at this point and have left a laying queen behind to continue on. It’s not uncommon for a hive to be left queenless after swarming takes place. So I think I am rather fortunate in that regard. Of the swarms that I have caught, I believe most have come from my own apiary. This year I have observed several swarms leave my hives and I have even caught pictures of tiny swarms on trail cams. Two swarms in particular I managed to snag as they were collecting themselves before moving on to their final location. One of which, was extremely large hanging on a maple tree. I suspect that I have caught somewhere around a third to half of the swarms that have left my apiary. Some of the swarms I have observed were much smaller than I would have expected. Two in particular were so small (probably about the size of a baseball) they collapsed shortly after the spring nectar flow ended.

1.25.21 – End of Season 2020

The sources of nectar basically shut down towards the end of October. Usually that’s due to temperatures dropping and the bloom cycle coming to an end. From what I have noticed the Asters and the Sea Myrtle (Baccharis halimifolia) look to be about the last two plants that honeybees can work in this part of the state. 2020 was very mild in the fall so that bloom may have extended into parts of November.

Now into 2021 – Getting more in Depth

I meant to get this posting out in 2020, always so much to do. Up to this point in the journal I have been a bit broad on topics. Generally covering my observations and the conditions of honeybees in my area of the state. Moving forward, however, I am looking to go into greater depth on a specific topic as I think that will be of greater value.

Thinking about Honeybee Forage

I find myself reflecting more and more on sources of forage rather than what the bees are doing in the hive. At a certain point in beekeeping one can gauge how a colony is doing by looking at the entrance. Thus, not as much need to open the hive, which the bees appreciate. That assumes everything is looking fine and dandy at the entrance. The bees prefer I left them alone anyways, which is fine with me.

Good number of bees suggests a strong colony

I have mentioned before that the nectar flows in my area, central North Carolina, are really good in the spring. That is there is lots of bloom in April and May. Tulip Poplar is the main spring nectar source for pretty much all of the state. June is an ok month while July and most of August being the worst months (in my area), apart from the winter months that is. The summer months can be very hard on a colony. It’s very easy for a colony to deplete is resources during this period, as forage is bare. Small colonies and later swarms really limp along during this time. Cotton fields are a boon for those colonies within range as that eases that summer dearth pressure. In my county however there is little cotton grown, and none of it is near my hives.

Early September is decent moving to good around mid-month. From the middle of September to the end of the season the bloom can be really good. There are lots of native fall blooming plants in this part of the state. Assuming the weather holds, which can be iffy as its hurricane season. The fall flow can be an excellent period for forage. This year was the best fall flow that I have experienced in terms of the number and variety of floral sources. Native bloom was rampant this year, I suspect due to higher rainfall in the preceding months.

These bloom observations are generalities, and as such beekeeping is local. A colony has a forage range around 2 miles, so whatever is blooming in that zone may deviate from the observed norm. For instance, colonies near sources of water could benefit from large stands of Galberry (Ilex glabra) or Buttonbush, so it just depends on where the hives are placed.

Planting for a Stationary Beekeeping Model

I am building a stationary beekeeping model, so concerning forage I am looking to plant species that supplement the less favorable bloom periods. A migratory beekeeping model has hives moving around chasing various nectar flows. Two reasons for not moving my hives… one I am looking to flood my area with swarms. Over time this will be my main method for colony expansion. The second is that I am interested in seeing if super-sized hives will survive long term. Mega hives (24 deep frames +) are much more efficient foragers, though they are a hassle to move around. Size, weight, and lots of bees factor into that. I have considered a dedicated trailering system for moving large hives to capitalize on Clary Sage flows. Though that still requires a lot of labor in moving, managing, and they aren’t going to be growing Clary Sage for a few years. At this time I would rather put that time and capital into developing the land around the beehives.

Large hives have brood areas spanning across three boxes, typically deep boxes.

As far as planting for nectar flow goes, I think it’s practically pointless to plant anything that is going to bloom in the spring. When the poplars are blooming, the bees don’t seem to care about other plants as much. The poplar flow is just that good. While there are a good number of fall blooming plants in my forage zone, I would like to see greater density of those plants. So… practically speaking this has me targeting species that are going to bloom from late May to the end of August. Additional expansion of species that bloom in September and October I believe is also beneficial.

Over the last few years I have been studying what honey bees seem to work. Honeybees can be very deceptive in their foraging. Some of that is due to the time of day that a plant’s nectar flows. Nectar doesn’t constantly flow when a plant flowers. Each species has their own behaviors, i.e. nectar flow time, duration, nectar amount, etc. Sometimes bees work a flower that pushes nectar until the flower is pollinated. Not all plants are like that, though some are. Honeybees are also selective, favoring the most desirable plant at any given time. For example… I have often wondered why I almost never see honeybees work Goldenrod. Goldenrod is a major nectar source in lots of places, but I never see my bees working it. Other parts of the state that is not the case, so it leads me to conclude there is something blooming that they are more interested in. Currently I believe honeybees prefer working the Asters, which I do see them work vigorously.

I think it wise to select native blooming species. Native bloomers are adapted to a local area, naturalize better, and don’t out compete in ways that some invasive species do. Wisteria comes to mind here, I have an extreme amount of it even choking out large pine trees. There are a few plants in my zone that bees work with vigor that don’t seem to garner the same attention as other more well-known bloomers (e.g. Southern Crownbeard). Basically, look for plants that are mobbed by bees rather than just a couple. So, I think it pays to see what’s blooming around you and follow those ques. In terms of planting, it seems wise to plant trees, shrubs, and wildflower perennials. Trees and shrubs push more nectar though they are going to take many years to get established. Perennial wildflowers can get going in one season, so I think it pays to do all of the above. From a bee health standpoint a greater variety of blooming plants is also more desirable.

Honeybee Planting Projects for 2021

I originally wrote this a couple months ago and my plans have shifted somewhat. Factors that play into that are reading Dirt to Soil by Gabe Brown and grabbing a couple American Persimmons to try and germinate.

Lets look at the first – Dirt to Soil

Persimmon seeds undergoing artificially cold stratification

I picked up a mini fridge so that I could artificially cold stratify some wildflower seeds this year. I think that my previous years attempts seeds haven’t broken seed dormancy. The winter in 2019-2020 was fairly mild by our norms. Therefore, I haven’t had much luck with my wildflowers germinating that have dormancy mechanisms as of yet.

Most perennial wildflowers require cold stratification of some degree. Once stratified, I intend to broadcast most of the seed around March 1st and try to germinate others for seedling transplant. Here are my lists prior to reading Dirt to Soil, they were intended for a couple different locations based on sunlight and moisture.

Sun Mix – Butterfly Weed (Asclepias tuberosa), Downy Wood Mint (Blephilia ciliate), Hoary Vervain (Verbena stricta), Blazing Star (Liatris spicata), Coneflower (Echinacea purpurea), Nodding Onion (Allium cernuum), Rattlesnake Master (Eryngium yuccifolium), Blue Sage (Salvia Azurea), Spotted Bee Balm (Mondara punctata), Frost Aster (Symphyotrichum pilosum), Yellow Crownbeard (Verbesina occidentalis), Aromatic Aster (Symphyotrichum oblongifolium)

Shade Mix – Virginia Waterleaf (Hydrophyllum virginianum), Hairy Wood Mint (Blephilia hirsute), Late Figwort (Scrophularia marilandica), Shorts Aster (Symphyotrichum shortii)

Wet Mix – Mountain Mint (Pycnanthemum virginianum), Joe Pye Weed (Eutrochium maculatum), Wild Goldenglow (Rudbeckia laciniata), Ironweed (Vernonia noveboracensis)

Gabe Brown talks about regenerative agriculture which focuses on soil health. The five tenants he espouses are no (minimal if any) tillage, no chemicals (that includes fertilizers), protect the soil with living root, integrate animals, and increase biodiversity. Brown’s main focus is soil health which considers the soil structure, bacteria, fungi, and various other microorganisms that interact with plant root systems. He also recommends slowly stepping down the chemical applications as it is difficult to completely remove them all at once.

I am currently of the opinion that these practices would contribute to gains in overall bee health. Additionally, I have a suspicion that all be products would be more nutritious and the flavor would improve. Gabe Brown seeds in cover crops of around 12 difference species and knows others that push that to around two dozen species. Those covers are intended to help return carbon to the soil via the grasses and grains, nitrogen through the legumes, and reduce compaction from the long taproot species of plants. The latter helps with improving water infiltration rates, resulting in greater drought tolerance.

Now reviewing my list, a good start but I needed some legumes/nitrogen fixers and more species (variety) in the shade and wet mixes. Nitrogen fixing plants are those that have symbiotic relationships with bacteria that convert atmospheric nitrogen into nitrogen available for the host plant. This occurs in the soil at the root level where nodules form on the host plant root system. It’s a way of getting nitrogen into the soil without the use of synthesized fertilizer. Clovers, beans, and peas are the most common nitrogen fixers. Dutch Clover (Trifolium repens), Sampson’s Snakeroot (Orbexilum pedunculatum), Wild Lupine (Lupinus perennis), Pointed-Leaved Tick Trefoil (Desmodium glutinosum), Wild White Indigo (Baptisa Alba), Partridge Pea (Chamaecrista fasciculata), Slender Bush Clover (Lespedeza virginica), and Naked-Flowered Tick Trefoil (Hylodesmum nudiflorum) are all native perennials I have found for this region that fix atmospheric nitrogen.

Some limited grasses could be a good addition in certain spots as well. Here is the sun and wet mixes with a few more additions. The wet areas in my location don’t have the best sun so I am not focusing a lot on those sections this year. The shade mix needed some work though and this actually led me to my second shift in plans.

Sun Mix additions – Wild Lupine, Partridge Pea, Wild White Indigo, Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale), Dutch Clover, Stout Blue-Eyed Grass (Sisyrinchium angustifolium), and Fescue.

Wet Mix Additions – Dutch Clover, Wild White Indigo, Mistflower (Conoclinium coelestinum), Golden Alexanders (Zizia aurea), Ohio Spiderwort (Tradescantia ohiensis), Wood Betony (Pedicularis canadensis), Rose Milkweed (Asclepias incarnata), Smooth Blue Aster (Symphyotrichum laeve), Fescue, and River Oats (Chasmanthium latifolium).

Woodland Wildflowers for Honeybees?

It occurred to me, if I was able to successfully develop a stand of wildflowers in shady locations then that may be the best direction to focus energies. Most of the land around my bees is wooded, so there is more shade than sun. Perhaps its possible to incorporate trees and shrubs into the plan as well, that’s where the Persimmon trees come in. I have been planting Basswood trees already. My dad was saying that he talked to beekeeper that was of the opinion that his bees made large crops of honey off Persimmons. Trees and shrubs are bigger producers of nectar, they just take longer to get established. On the order of years as opposed to a year or two with wildflower plantings.

I never really looked into the shade locations previously as, one it was hard to find appropriate plants for those locations. Secondly, I just assumed those plants didn’t really exist. Honestly, if you go into Lowes or Home Depot all you see in their shade sections is Hydrangeas, Azaleas, Ivy, and Ferns. Quite frustrating why plant options are so limited. Other garden centers, and nurseries I have found aren’t that much better in terms of selection. It took a while to research, but it does appear there are quite a few species that could work in this situation. The seed dormancy mechanism in some shade tolerant species are a bit trickier to break (double dormancy) so I am starting off with easier ones for now.

The plan is to trial a shade plot and see what comes up. If successful then I intend thin out the woodland understory, primarily oaks, sweet gums, and small pines. I was already doing this to backfill with Basswoods anyways. Limb up the larger trees (mainly Pines) and plant Persimmon trees in addition to the Basswoods. The land near my bees had several spots that were farmed conventionally around 20-30 years ago so those areas are stands of pines now. Other spots are typical deciduous stands of trees (Sweet Gum, Red Maple, Tulip Poplar, Red Oak, Winged Elm, Holly) and the occasional Hackberry, Persimmon, Sourwood, and Sassafras tree.

I intend a shade tolerant wildflower mix to grow under the canopy of existing and newly planted trees. Additions to the shade mix are more varieties, nitrogen fixers, and some grasses. It’s intended to be a nectary so I don’t want to get too heavy on the grasses. Some of these plants are well known to have honeybees work them, such as Joe Pye Weed. Others, more difficult to find pertinent forage information. Though, these difficult flowers often have shapes and profiles that are similar to favored honeybee flowers. For example, Spikenard (Aralia racemosa) has a flower that looks like a honeybee flower. However, it is difficult to find visual evidence of honeybees working it. That being said it is in the same family as Devil’s Walking Stick (Aralia spinosa) which I have seen honeybees work in this area. The two plants have similar flowers so it wouldn’t surprise me to see honeybees use Spikenard as a forage source.

Seed costs limit my budget to do a big broadcasting so I am looking to germinate about half the list for transplanting. There are few suppliers and even less demand for perennial shade wildflowers so in general the seed cost is higher and available in more limited quantities. I collect local seed and have purchased seed from Prairie Moon Nursery, American Meadows, Outside Pride, Treehelp.com, Native American Seed, and Eden Brothers.

Revised Shade Mix – Dutch Clover, Virginia Waterleaf, Foam Flower (Tiarella cordifolia), Persimmon (Diospyros virginiana), Basswood (Tilia Americana), Hairy Wood Mint, Tall Bellflower (Campanula americana), Pointed Leaved Tick Trefoil (Desmodium glutinosum), Sweet Joe Pye Weed (Eutrochium purpureum), Wild Golden Glow, Wood Gray Sedge (Carex grisea), Nodding Fescue (Festuca subverticillata), Slender Bush Clover, Spikenard, Elm-Leaved Goldenrod (Solidago ulmifolia), Late Figwort, White Wood Aster (Eurybia divaricata), Big Leaved Aster (Eurybia macrophylla), Shorts Aster, Frostweed (Verbesina Virginica).

9.18.20 – The Fall Nectar Flow

Bloom Report – False Sunflower, Goldenrod, Aster, Ironweed, Clover, Wild Sunflower, Spotted Bee Balm, Blue Sage, Southern Crownbeard

False Sunflower – Wake County, NC

The Fall nectar flow is mainly made up of golden rod and aster blooms, though there are a number of other flowers that contribute as well. Right now there are hordes of false sunflower in the easement, power, and road right of ways. This nectar flow basically starts around the first of September and lasts till about mid-October. The weather can paly havoc though, its not unheard of for a hurricane or string of them to come in and wreck the entire nectar flow.

This is a really important time for honey bee colonies as it’s the last push to pack nectar and pollen for the winter. Hives typically push out drones beginning in August and the colony will begin filling up the brood areas with nectar. It’s a good idea to removed extra space on a hive, honeybees generally will not draw out comb this time of year. Thus, its important to give a hive drawn comb frames if any are required right now. Reducing the space congests a hive and helps them focus on getting their hive set up for winter.

Planting for Summer/Fall Nectar flow

I have mentioned a few times that the summers are hard in this part of the state, in terms of nectar flow. To improve this situation I have been planting and managing the borders of my bee yard. In this bee yard I have been removing small understory trees to improve light and clearing the woodline edges. If it is a plant that doesn’t produce nectar for bees in the June-October time frame its got to go. Any beneficial plant is promoted to encourage greater growth and spread.

First year growth on Shining Sumac to be transplanted

In practice this means about 8 ft or so of tree line edges are left unmowed from March till Thanksgiving. Thanks to some volunteer Shining Sumac I am working to spread Sumac on back edge of this wildflower buffer. The idea is that I have taller Sumac or other large shrubs growing behind a mix of wildflowers. Sumac spreads by rhizome so all of the first year shoots are easily chopped out as the roots are only about an inch or two deep. Last fall I chopped about 50 first year shoots out and plugged them in in other spots around the property. About half survived that transplanting, some grew out of the top and others grew back out from the roots this year.

The mix of wildflowers varies depending on sunlight and soil moisture conditions. Most of my borders are full sun with medium to dry soils. I am developing a wildflower mix of plants that are native to North Carolina. For these locations I am planting Butterfly weed, Downy Wood Mint, Coneflower, Blazing Star, Mountain Mint, Hoary Vervain, Nodding Onion, Rattlesnake Master, False Sunflower, Blue Sage, Spotted Bee Balm, Golden Rod, Smooth Blue Aster, and Southern Crownbeard. I collect native seeds and use them to spread on my property to reduce the cost. Goldenrod, Asters, Wild Sunflowers, and Southern Crownbeard are easy to find this time of year to collect. I have purchased seeds from both Prairemoon Nursery, American Meadows, and Park Seed Co., they are reputable sources of seed.

Stand of Ironweed – Wake County, NC

I found a couple small patches of Ironweed this year, which is coming up in some ditch lines nearby. It’s a really pretty flower, so I am collecting those seed heads this year too. Given that I am looking to propogate Ironweed along with some Mountain Mint, Wild Golden Glow, and Sweet Joe Pye Weed in a couple wetter spots. Lastly, I have a border on the south side of a field that gets a lot of shade, but isn’t wet. For those shady spots I am going to see if I can get some Hairy Wood Mint, Shorts Aster, and Late Figwort to grow. I am targeting wildflower bloom periods primarily from June to September as the dearth is hardest in this area during this period.

Get Wildflower Seeds where you can

Goldenrod bloom getting close to peak

There are a lot of wildflowers that come up in ditch lines, field edges, and rite of ways. I have been collecting seeds from those plants and scattering then all around my bee yard for the last few years. The wildflower spread hasn’t been wildly successful yet, mostly some expansion of Goldenrod and some Milkweed. Given the milder winters the last couple of years I suspect that a number of those seeds haven’t broken their dormancy period. As it turns out most perennial wildflower require a period of cold temperatures to break the seeds dormancy. These cold periods are usually one to two months, but some plants require longer than that.

First year planting of Spotted Bee Balm

This year I am going to artificially cold stratify my seeds before I sow them. In years passed I like to sow after Thanksgiving, though germination has been limited. A portion of those seeds will probably come up at some point in time, though it may take another year or so for the seed to be viable. I am looking to sow a portion of my seeds in February following cold stratifying and reserve others to germinate and plug in after the date of last frost in the spring. Hopefully I will have more luck next year.

9.1.20 – Finishing out the Summer

Unidentified Wildflower Bloom

In these parts the summer is very tough. Unless you happen to be in some areas with a few specific nectar flows there is very little for the bees to forage on. There are a plethora of wildflowers around that honeybees forage on but often those wildflower stands aren’t large. Much of the time you would probably not even know those wildflowers are there, they are that nondescript.

In North Carolina, if you can put bees on cotton then you are in good shape. Cotton planting has been late and staggered the last few years so what was usually a 4-5 week bloom period can now stretch into 6-7 weeks. Traditionally, cotton blooms around the 4th of July, though in recent years the start has generally be about two weeks after that. Cotton fields frequently have borders of fall wildflowers, usually goldenrod, false sunflower, aster, and crownbeard. Those wildflower stands benefit from fertilizer runoff and full sun. I have seen cotton blooms continue right into September right when all the fall wildflowers are starting to turn on.

How are my Bee hives?

I started this year with five surviving hives, one of which was the last treated hive I brought up to Wake County. That hive barely had any bees left but managed to hold on for most of the year. It finally broke down, and got robbed out, which wasn’t any surprise to me. Through swarm catching and splitting I have about twenty hives in Wake County.

I split all the hives this year using the OTS (on the spot) method. Doing this I basically divide a box of bees into two boxes, using a Langstroth hive. Splitting a double deep hive I opted to use at least four frames (8 deep frames) to make a split. Make sure that both boxes have eggs in them, no need trying to find the queen. The box without a queen will raise a new queen, taking around 28 days to get a mated queen. I let a hive build up to two deep boxes and then split them evenly. The larger number of bees and congesting the bees helped a lot to raise a new queen in the first few days of being queenless. In years passed, using this method with only a few frames (2-3 frames) of bees resulted in several failed attempts at raising new queens. I think I only had one hive not raise a queen on the first attempt this year.

I split all the hives this year using the OTS (on the spot) method. Doing this I basically divide a box of bees into two boxes, using a Langstroth hive. Splitting a double deep hive I opted to use at least four frames (8 deep frames) to make a split. Make sure that both boxes have eggs in them, no need trying to find the queen. The box without a queen will raise a new queen, taking around 28 days to get a mated queen. I let a hive build up to two deep boxes and then split them evenly. The larger number of bees and congesting the bees helped a lot to raise a new queen in the first few days of being queenless. In years passed, using this method with only a few frames (2-3 frames) of bees resulted in several failed attempts at raising new queens. I think I only had one hive not raise a queen on the first attempt this year.

This year I split aggressively so most of the hives are small, most will finish off the year in the 8-14 (deep) frames range. That has made resource collecting difficult in the summer, since smaller hives have smaller foraging forces. I started feeding in mid-August to stimulate laying. It’s typical for laying in the summer to slow down due to the heat and lack of resources. There was also very little honey stored away since most of the hives were made or caught after the spring flow.

Feeding of Honey Bees

Eventually I would like to get the apiary to a point where feeding is not necessary. Feeding (simple syrup) I believe is not desirable for overall be health, but it is better than letting a small hive starve. Larger hives that starve out in the summer probably don’t have the desired genetics that I am looking for. Either way, I am feeding for now though I try to limit the amount that I do feed, mostly to small hives.

Top Feeder on a Double Deep Horizontal Hive

I believe there are a few shifts in management style required to have a hive that doesn’t need feeding in this area. Locally, the spring flow represents the bulk of honey put on a hive. In order for the honey bees to thrive in the summer I believe the bees should keep the first honey. Its fairly common for beekeepers to take too much honey off a hive after the spring flow. That usually has them feeding later in the year.

Leaving the first honey on a hive may result in hives that don’t produce excess yield. So its quite possible that more hives and larger hives may be required in order to have honey for sale. I would also like to split a hive only once per year. Making a split or even taking resources from one hive to support another is very taxing on a hive. This likely requires some hives just for honey production and others for breeding.

In a treatment free apiary this is difficult as the heavy mortality rates the first few years puts a lot of pressure to expand numbers. There are a few practices that aren’t ideal(feeding), that likely are required the first few years while developing survivor genetics. In my case I would be thrilled with a 50% survivor rate this winter (the second winter without chemicals). That would mean 10 hives to build up off of next year. Ten hives is still not a lot to expand off of and have dedicated honey hives. Though it certainly is better than starting with five hives.

6.15.20 – The start of the June dearth

Bloom Report – Ligustrum, Sourwood, Chaste Tree, Clover, Basswood, Buttonbush, Crape myrtle, Queen Anne’s Lace

Ligustrum Lucidium

The spring nectar flow wraps up quickly moving into the end of may and beginning of June. In Raleigh the most prevalent blooming bee plant (right now) appears to be Ligustrum (Privet). It’s not a terrific nectary but there certainly is a lot of it around here. Sourwood is also easily seen along the highways. In the piedmont there is actually a lot of sourwood but most of it is in the understory. I don’t think that it gets enough sunlight to bloom strongly. Basswood and Buttonbush are really nice blooming plants starting right about now, but those are typically localized to the mountains and waterways respectively. Lucky is the beehive that has them nearby right now. There are various other blooming flowers that you can see honeybees working, though there usually aren’t large stands of them.

June ushers in the dearth period in North Carolina. I.e. a time of limited or no major nectar flows. There are still plants blooming right now but the choices become much more limited. As such robbing is more prevalent. Meaning bees from one hive will rob honey from another. A really strong hive can actually overrun a smaller one. I had a mass of bees get in my garage a week or so ago as I had some juicy frames hanging around that some nearby bees found. That lasted for a day or so till they cleaned out all those frames. Honeybees really get in a frenzy this time of year if they find really abundant sugar sources. Click the image to see the video.

June ushers in the dearth period in North Carolina. I.e. a time of limited or no major nectar flows. There are still plants blooming right now but the choices become much more limited. As such robbing is more prevalent. Meaning bees from one hive will rob honey from another. A really strong hive can actually overrun a smaller one. I had a mass of bees get in my garage a week or so ago as I had some juicy frames hanging around that some nearby bees found. That lasted for a day or so till they cleaned out all those frames. Honeybees really get in a frenzy this time of year if they find really abundant sugar sources. Click the image to see the video.

Clary Sage 2020

We had 24 hives on Clary Sage this year in Chowan County, NC. I would consider this year rather mediocre to poor in terms of honey production. There were two weeks of prolonged rain during the peak of the bloom. Many beekeepers across the state reported a similar outcome. Given that most of the honey produced for market is spring honey I would wager that the availability of local honey is going to be down this year.

We had 24 hives on Clary Sage this year in Chowan County, NC. I would consider this year rather mediocre to poor in terms of honey production. There were two weeks of prolonged rain during the peak of the bloom. Many beekeepers across the state reported a similar outcome. Given that most of the honey produced for market is spring honey I would wager that the availability of local honey is going to be down this year.

When bees are inside the hive they consume their stored honey. A double hit as they aren’t foraging for new nectar as well. We went from extremely dry at this time last year to extremely wet this year. Around six of my hives swarmed out or crashed during this time. Its prime time for swarming so some of that was expected. Either way I am thankful for what we were able to harvest. We yielded around 300lbs of Clary Sage honey this year.

Clary Sage Bloom – Salvia Sclarea

If you are not familiar with Clary Sage Honey (click link for some history), I would consider it as one of the top tier variety honeys. It is lite in color/tone, slow to crystalize, and has some floral accents. In our region I would put it on par with Tupelo and Sourwood Honey. Unfortunately, this may be the last year that Clary Sage Honey will be available as there are rumblings that Avoca is shifting away from Clary Sage processing. The most recent rumor that I have heard is that Avoca is going to convert to hemp processing. Presumably they are looking to process hemp for CBD oil. The extraction process I think is similar to extracting the sclareol in Clary Sage. Clary Sage is planted in the fall so we will know then if Avoca issues contracts for next year or not.

June Swarm Update

The flood gates were opened In Wake county the first week of May. I caught five swarms that first week and have caught a small handful since then. All told I am currently at eight swarms this season in Wake County, and one in Halifax County. I have even caught a few swarms in my double deep swarm boxes. One in particular was one of the largest swarms I have ever caught, close to seven frames of bees. I am loading this swarm into the last bay of my swarm casting box.

The flood gates were opened In Wake county the first week of May. I caught five swarms that first week and have caught a small handful since then. All told I am currently at eight swarms this season in Wake County, and one in Halifax County. I have even caught a few swarms in my double deep swarm boxes. One in particular was one of the largest swarms I have ever caught, close to seven frames of bees. I am loading this swarm into the last bay of my swarm casting box.

Now that I have seen these double deep swarm boxes in action, I have some answers to my initial questions. They are indeed attractive to swarms, and the extra weight isn’t terrible. Though, I tend to hang the double deep boxes lower in a tree. Usually somewhere between four and six feet.

Now that I have seen these double deep swarm boxes in action, I have some answers to my initial questions. They are indeed attractive to swarms, and the extra weight isn’t terrible. Though, I tend to hang the double deep boxes lower in a tree. Usually somewhere between four and six feet.

That being said the dark color on them makes them much hotter than my other hives. I had to shim the top to vent the box, mitigating the bearding on the front of the hive. The opening size also appears to be restrictive, contributing to my heat issues. Venting is counterproductive to maintaining a high humid environment. Though it has lessened the bearding substantially, and the hive seems happier. A box with a high humidity environment is thought to hinder varroa reproduction rates. While that is good, the 90+ degree days in full sun don’t help the hive thermodynamics. I am considering moving the opening to the bottom of the box. There is a little bit of open space below the frames so I think that will help air and bee flow.

4.22.20 – Tracking the Nectar Flow for NC Honey

Honeybee on Collard Bloom

We all like North Carolina honey, and that honey comes from plant nectar. Honeybees don’t make honey, or at least less of it, when there isn’t much blooming. So, keeping bees really makes you pay attention to what is blooming at all times of the year. Before I kept bees, the native plant bloom was taking place but it was all in the background for me. In the past few weeks – Hollies, Black Cherry, Willow, Elm, and Wisteria have already bloomed. Blackberry, Tupelo and Poplar are currently in bloom.

Now in the fourth week of April, the Tulip Poplar flow is just starting here in the piedmont. I have seen some very mature poplars blooming for a little bit now. Though by and large the bloom hasn’t come into full swing. Back home, in the northeast part of the state, plants seem to bloom about 7-10 days behind the piedmont. As nectar flows go, the poplar bloom is strong as it typically lasts around three weeks. This lumps it in the category of major nectar flow. Most plants don’t bloom this long or produce as much nectar.

Large Photinia Serrulata

Generally speaking, plants that produce a major nectar flow tend to be trees, shrubs of decent size, or plants that grow in large swaths. Either a plant is large enough to push a lot of nectar or there are smaller plants that are more numerous. The majority of these plants tend to bloom in the spring time. As such, in our state, the spring is a good time for nectar flows. Many places however don’t see much nectar flow passed June. There is a summer dearth in most parts of the state. Dearth meaning a time of little nectar flow. This is also when robbing is the most abundant.

Most spots, especially rural areas, do have some fall flow. Primarily this is made up of Goldenrod, Aster, and a species of native Sunflower. That being said, location is everything. I find urban areas to have more limited nectar flows outside of the spring flow. Unsurprisingly, development has led to the depletion of a lot of forage. Nice weed free lawns in abundance don’t make things any better.

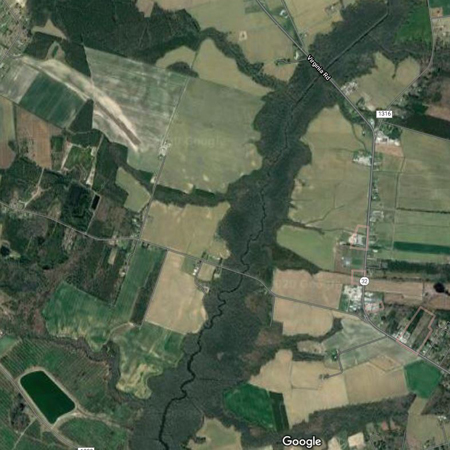

Back on the idea of location, it is possible to find areas that very localized honey flows take place. Keeping bees near lakes, or large waterways, can be beneficial as its possible to pick up nectar flows from Gallberry and Buttonbush. Sourwood in the mountains also comes to mind. Looking at this aerial near my hometown you can see the creek running up the center of the image. The area immediately surrounding the creek is low and swampy filled with very large Tupelo and Poplar trees. The cultivated areas adjacent to the tree lines are all usually filled with Sage, Cotton, and Soybeans. Additionally, the cultivated areas typically have stands of fall blooming plants that receive fertilizer runoff and strong daylight. Those fall blooming stands can be large, dense, and are located around most fields. It’s quite possible in many parts of eastern North Carolina to hit 3-5 major nectar flows. That’s alot of NC honey.

Back on the idea of location, it is possible to find areas that very localized honey flows take place. Keeping bees near lakes, or large waterways, can be beneficial as its possible to pick up nectar flows from Gallberry and Buttonbush. Sourwood in the mountains also comes to mind. Looking at this aerial near my hometown you can see the creek running up the center of the image. The area immediately surrounding the creek is low and swampy filled with very large Tupelo and Poplar trees. The cultivated areas adjacent to the tree lines are all usually filled with Sage, Cotton, and Soybeans. Additionally, the cultivated areas typically have stands of fall blooming plants that receive fertilizer runoff and strong daylight. Those fall blooming stands can be large, dense, and are located around most fields. It’s quite possible in many parts of eastern North Carolina to hit 3-5 major nectar flows. That’s alot of NC honey.

Clary Sage Field early April

This year the sage field where we moved bees happens to be near this creek area. Clary Sage typically blooms around the beginning of May and tends to last the whole month. At the time we moved the hives we are likely to pick up the Tupelo bloom first. Tulip poplar and Clary Sage will follow in the coming weeks. All told there should be strong nectar flow for seven to eight weeks. Last year we had about sixteen hives for the sage flow. It was very dry and hot during the sage season last year, so not ideal conditions. The honey was very thick coming out of the comb. This year we have around 30 colonies so we will see what happens.

Hives set up on Sage – April 2020

The piedmont bee yard is located near a lake, so in addition to the strong spring bloom I know there is some buttonbush growing around the lake. This helps produce a nectar flow in the June time frame. Outside of the sumac that blooms in late July, the summer dearth is pretty heavy. There is a fall flow, though honeybees are mysterious; at times it’s obvious what plants they are working and most other times it’s not. Currently it’s hard to gauge the strength of the smaller summer flows and the fall flow in the piedmont.

3.27.20 – Double Deep Swarm Box

The Sunflower “Swarm Caster” painted by my daughter

Last year I started to experiment with insulated double deep frame hives, i.e. Lazutin hive. The idea is this hive style promises to be superior to stacking (Langstroth) hives, but I’ll save that for another time. If interested, read Beekeeping with a Smile. Building on this concept, I made a double deep insulated hive that is split into three 6 frame sections just for the purpose of casting swarms. I am looking to develop this idea to help automate the breeding process as swarms don’t require any beekeeper manipulation and they ramp up more quickly than splits. “Ramp up” meaning the queen is already laying and the swarm comes with the right number of bees/resources to build out quickly.

A double deep frame is basically two standard deep frames joined together. Most people join the two frames top to bottom. I opted to go side to side and fashion them with a new top bar as this still allows me to use my deep frames without modifying them. Additionally, I can still use my extraction equipment. The bottom frame in the top to bottom method usually requires cutting the ears off the bottom frame.

A double deep frame is basically two standard deep frames joined together. Most people join the two frames top to bottom. I opted to go side to side and fashion them with a new top bar as this still allows me to use my deep frames without modifying them. Additionally, I can still use my extraction equipment. The bottom frame in the top to bottom method usually requires cutting the ears off the bottom frame.

This year I made several swarm boxes that utilize a double deep frame and I decided to insulate them. A standard 40 liter swarm box usually holds five frames and has several inches of space below the frames. To accommodate a double deep frame it only requires the swarm box to be a touch deeper. Using approximately the same volume I can fill that box with the equivalent of 8 deep frames. This is a plus for me as I have had swarms move in and build right on the bottom of the frames and not in the frames themselves.

The main drawback in this build was the weight. Since I made a double wall box with insulation in between it increased the width of the box and its weight. The first set of boxes I made actually hold 6 double frames and those boxes really are heavy. I suspect they will be used more for making splits in the future. Originally I was thinking that i needed larger hives to overwinter more successfully, thus the 6 frame boxes. I have since learned (reading Kirk Webster) that there are lots of people that over winter nucs in a 4 over 4 configuration very well. Even in more northern climates. So ideally a 4 double frame box is a better choice, and is what I made on my last build run.

The main drawback in this build was the weight. Since I made a double wall box with insulation in between it increased the width of the box and its weight. The first set of boxes I made actually hold 6 double frames and those boxes really are heavy. I suspect they will be used more for making splits in the future. Originally I was thinking that i needed larger hives to overwinter more successfully, thus the 6 frame boxes. I have since learned (reading Kirk Webster) that there are lots of people that over winter nucs in a 4 over 4 configuration very well. Even in more northern climates. So ideally a 4 double frame box is a better choice, and is what I made on my last build run.

So… why insulate the swarm box at all, basically no one does this? What I would like to achieve is a condition where I can catch a swarm and have them overwinter in that box. This minimizes the amount of beekeeper intervention. In the future, it also allows me to sell overwintered colonies more easily as the whole colony and box could be sold together. The insulation also helps the colony thrive during the season and overwintering.

So… why insulate the swarm box at all, basically no one does this? What I would like to achieve is a condition where I can catch a swarm and have them overwinter in that box. This minimizes the amount of beekeeper intervention. In the future, it also allows me to sell overwintered colonies more easily as the whole colony and box could be sold together. The insulation also helps the colony thrive during the season and overwintering.

Advantages of double frame swarm box as I see them…

-

More frames so greater flexibility in recovering a swarm before it fills up the box or builds comb in places you don’t want.

-

Due to the space more flexibility in placing swarm boxes in more distant locations.

-

Insulation and frame style better for overwintering.

-

May not be necessary to move the hive out of the box (or split), especially for mid to late season swarms.

The questions/problems I am looking to have answered this year are…

-

Is this box style attractive to a swarm? I don’t see why it wouldn’t be… but if a swarm won’t move in then its a moot point.

-

Will early swarms build up enough so that they run out of room? Will they need to be split mid summer?

-

Is the weight of the box too big of an issue?

3.24.20 – Gearing up for Swarm Catching

varroa mite from sciencemag.org

Treatment free beekeeping is basically a management style. One that decides there will be no treatments of any kind applied to a honey bee hive. In its strictest form, some consider feeding bees a treatment as well. The majority of bee keepers put pesticides or other “organic” compounds on their hives mainly for the management of varroa destructor. The varroa mite is a parasite that feeds and reproduces on honey bees/larva and can overrun a hive. A hive or apiary run in a treatment free style relies upon developing survivor genetics, and as such most are very active in breeding and swarm catching.

It is common for an apiary to take many years to develop in a treatment free style as hive mortality rates are usually pretty high in the first couple of years. Its been reported by many that first year mortality is 70-90% of colonies and then gradually improves as the beekeeper splits and breeds from the surviving hives. I personally am expecting around 3/4 loss the first year, 1/2 the second, 1/3, 1/4, and so on… This passed winter was the first season where I haven’t moved the hives during the year and at the peak I had 16 colonies during the summer of 2019. I overwintered 13 colonies with 5 surviving the winter. My mortality percentages look to be right in line with expectation. Of the survivor colonies, two were swarms caught in Wake county, two were colonies I raised, and the last a treated colony that I split in the summer. The formerly treated colony looks to have barely held on so we will see if there are survivor genetics there.

Eastern NC Honeybee Swarm

Spring is about to set in and I am back into expansion mode, which means splitting of surviving hives and swarm catching. So what is swarm catching? Honeybees make two things, honey and more bees. A colony feels cramped when it fills up all the space in its cavity with said bees and honey. A cavity in this case is void in a tree (most common), rock face, ground, house/structure, or a hive box. When that happens a colony raises a new queen to take over and the old queen leaves with a portion of the colony to go find another space to fill up. In our area (March-September) there are swarms flying around that most of us never even realize are there.

Catching a swarm is fairly simplistic. The idea is to create an attractive home for the swarm to move in. In practice this is making a box and hanging it in a tree. Scout bees find the new location and if it is attractive then a swarm can move in. A swarm box typically has a 40 liters volume. Usually holds 5 frames, and is baited with lemongrass oil. Lemongrass oil mimics the queen pheromone which is attractive to scout bees. The idea is to make the box smell like bees have lived there before. Adding old brood comb, facing the box opening to the south, and locating the swarm box near a water source increase the odds of catching a swarm. Some advocate hanging the box high in a tree, although there are lots of people that have caught swarms low to the ground and even baiting old hives in their apiary.